Structure stories

A needle in a haystack

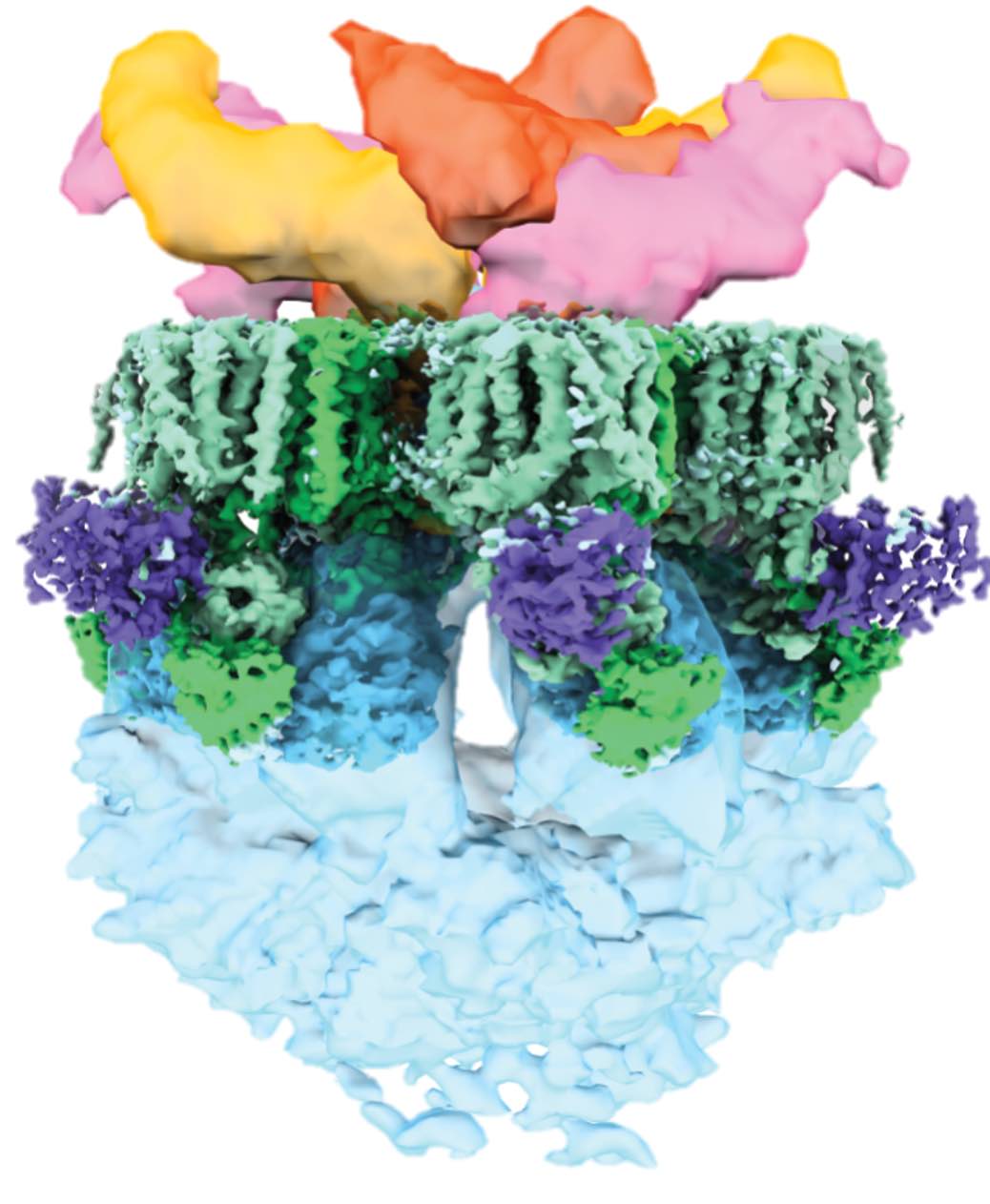

The model was automatically released by the wwPDB after a standard 1 year embargo and immediately attracted a lot of attention. An in situ cryo-ET reconstruction of a light-harvesting megacomplex from red algae; 37MDa, 1,792 aa chains, 305,000 residues and 2.5M non-H atoms. This huge model was undoubtedly a real challenge to build. It also proved to be a challenge for the wwPDB validation tools; the model remains unvalidated.

The model was automatically released by the wwPDB after a standard 1 year embargo and immediately attracted a lot of attention. An in situ cryo-ET reconstruction of a light-harvesting megacomplex from red algae; 37MDa, 1,792 aa chains, 305,000 residues and 2.5M non-H atoms. This huge model was undoubtedly a real challenge to build. It also proved to be a challenge for the wwPDB validation tools; the model remains unvalidated.

The good news is that the model can be validated easily using checkMySequence. In about an hour, the program finds several sequence assignment and map-fit issues. One of them is particularly interesting given my background in crystallography.

Molecular Replacement (MR) is the most widely used method for solving crystal structures. It provides a rough model of the crystal structure that is later iteratively improved. It’s much simpler than experimental phasing techniques, but requires a model that is very similar to the unknown macromolecule in the crystal. Usually a close homologue. As the PDB got bigger (even before AlphaFold2 came out), proteins with no known homologues became relatively rare. However, there were still cases of proteins that required experimental phasing. Once their structures were solved, it was often found that there are similar ones in the PDB already. But sequence similarity was too low to allow for identification.

The light-harvesting megacomplex turned out to contain two almost identical proteins (0.6 Å rmsd) with only 60% sequence identity, which were swapped in the model. Another example of identical proteins with low sequence similarity I faced in a short time. A protein feature desired for MR that can lead to hard-to-detect errors in EM. Remember to check your models with checkMySequence!

PDB id: 7Y7A

-

You, X., Zhang, X., Cheng, J., Xiao, Y., Ma, J., Sun, S., … & Sui, S. F. (2023). In situ structure of the red algal phycobilisome–PSII–PSI–LHC megacomplex. Nature, 616(7955), 199-206. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-05831-0

-

Sierk, M. L., & Kleywegt, G. J. (2004). Deja vu all over again: finding and analyzing protein structure similarities. Structure, 12(12), 2103-2111. doi:10.1016/j.str.2004.09.016

A tale of two dehydrogenases

I was contacted by Panos Kastritis from the University of Halle-Wittenberg who needed help interpreting three cryo-EM reconstructions from native C. thermophilum cell extracts. All of them had very characteristic tertiary structures and seemed easy to identify. In addition, AlphaFold2, which was released at about the same time, gave excellent predictions for all the targets. It looked like a straightforward model building task.

I was contacted by Panos Kastritis from the University of Halle-Wittenberg who needed help interpreting three cryo-EM reconstructions from native C. thermophilum cell extracts. All of them had very characteristic tertiary structures and seemed easy to identify. In addition, AlphaFold2, which was released at about the same time, gave excellent predictions for all the targets. It looked like a straightforward model building task.

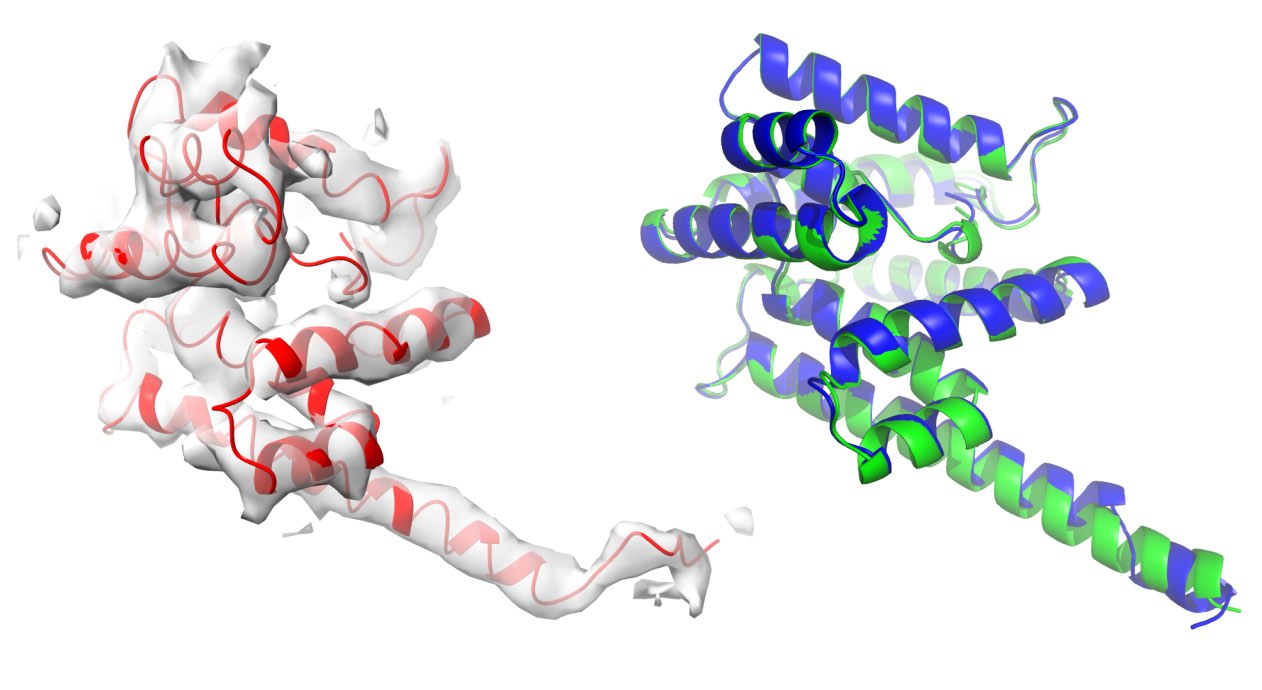

After building the initial models, I checked them with a prototype of checkMySequence, a sequence assignment validation program I was working on at the time. Surprisingly, the program identified a problem with the sequence of one of the models. It was completely wrong, even though the model seemed to fit the map perfectly.

It turned out that there are two variants of oxoglutarate dehydrogenases in the C. thermophilum proteome. They have very similar structures (1.5Å rmsd), but share only 22% of the sequence. They are visually indistinguishable based on the 4.4Å resolution map. To resolve the ambiguity, I predicted both structures with AlphaFold2, fitted them to the map, and used for sequence identification with findMySequence. The program assigned the same sequence variant to both backbone models, clearly confirming the identity of the protein.

If you can get rough fit of a predicted model to a reconstruction, findMySequence will help you identify a protein even if no side chains are visible. It’s a pretty powerful approach!

- Skalidis, Kyrilis, Tüting, Hamdi, Chojnowski, & Kastritis (2022). Cryo-EM and artificial intelligence visualize endogenous protein community members. Structure, 30(4), 575-589. doi:10.1016/j.str.2022.01.001

ESX-5 Type VII Secretion System

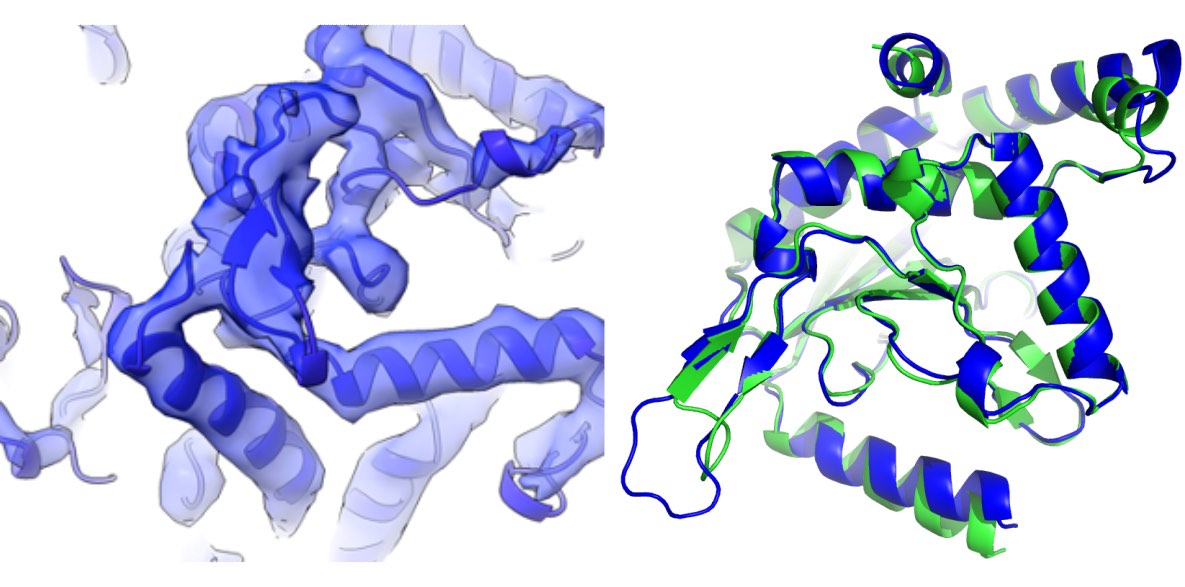

The very last cryo-EM structure I built without AlphaFold2. It required all the tricks including focused refinement, de novo model tracing, MX, and integrative modelling to interpret the data. The most interesting part of the story is that we were (technically) scooped by a group working right next door. However, their structure corresponds to different pore conformations than ours (closed versus open), which gives some intriguing new insights into how the complex works.

Fascinating project pursued virtually during covid-19 pandemic together with a great team of friends from EMBL!

The very last cryo-EM structure I built without AlphaFold2. It required all the tricks including focused refinement, de novo model tracing, MX, and integrative modelling to interpret the data. The most interesting part of the story is that we were (technically) scooped by a group working right next door. However, their structure corresponds to different pore conformations than ours (closed versus open), which gives some intriguing new insights into how the complex works.

Fascinating project pursued virtually during covid-19 pandemic together with a great team of friends from EMBL!

PDB id: 7B9S

- Beckham *, Ritter *, Chojnowski*, et al. (2021). Structure of the mycobacterial ESX-5 type VII secretion system pore complex. Science advances, 7(26), eabg9923.doi:10.1126/sciadv.abg9923

High resolutiuon strcuture of purine nucleoside phosphorylase

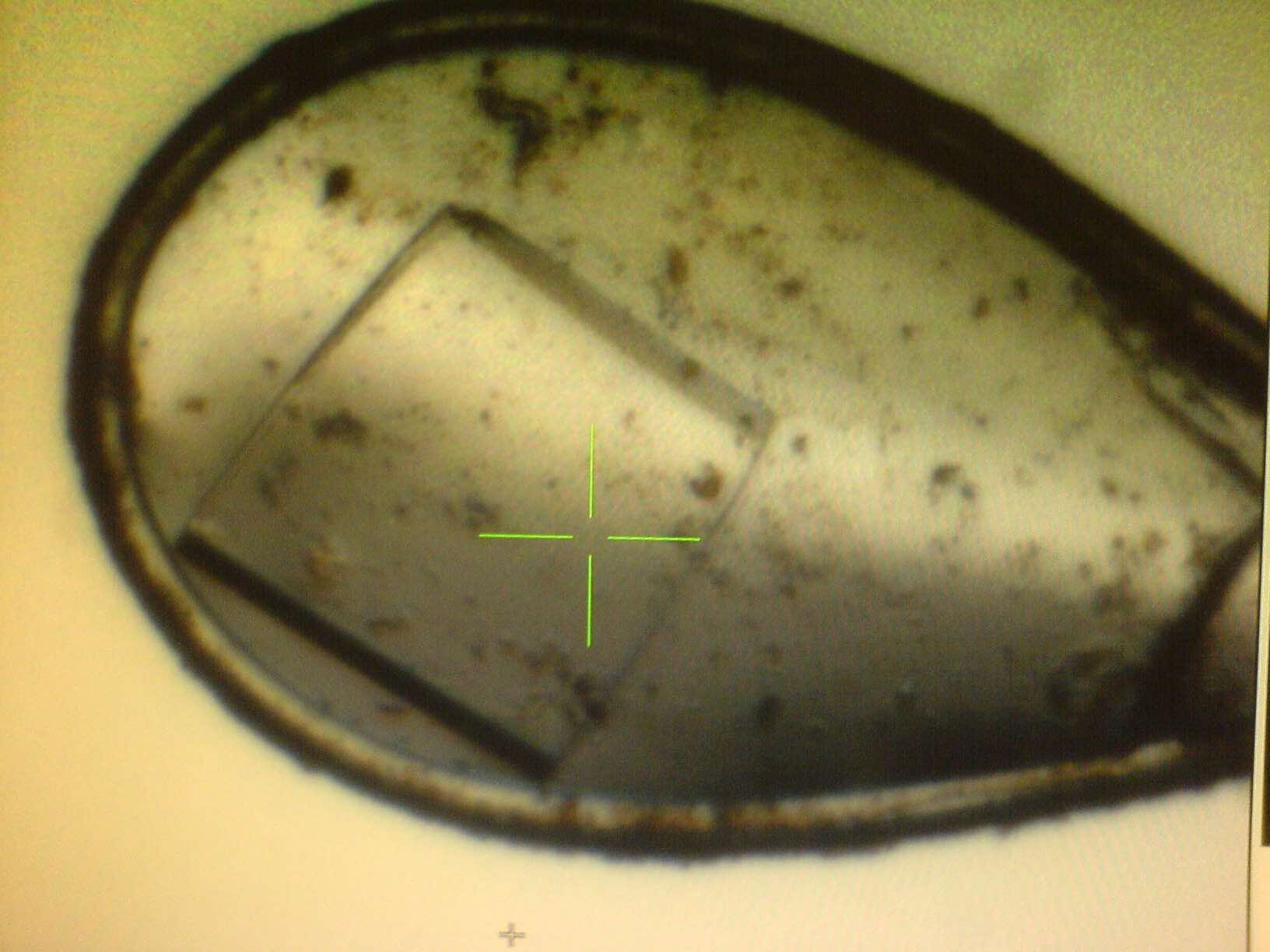

The very first crystal structure I solved. High-resolution (1.45 Å) structure models can be a pain to build (all those alternative conformations!), but the beautiful maps were a great help to a structural biology noob like me at the time. It was also the first model in the lab built using COOT, a new development back then. It quickly replaced O and made SGIs obsolete.

The very first crystal structure I solved. High-resolution (1.45 Å) structure models can be a pain to build (all those alternative conformations!), but the beautiful maps were a great help to a structural biology noob like me at the time. It was also the first model in the lab built using COOT, a new development back then. It quickly replaced O and made SGIs obsolete.

Picture on the left shows a PNP crystal during data collection at a non-existent storage ring DORIS at DESY, Hamburg. Cryo-jet has blown out most buffer from a too spacious loop, but the crystal still diffracted up to the edge of a detector.

PDB id: 3FUC

- Chojnowski, Breer, Narczyk, Wielgus-Kutrowska, et al. (2010). 1.45 Å resolution crystal structure of recombinant PNP in complex with a pM multisubstrate analogue inhibitor bearing one feature of the postulated transition state. Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 391(1), 703-708. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.11.124